Passion AR

* by Alfredo Di Pietro - www.nuke.nonsoloaudiofili.com

The Myth AR 3a

Historically, that’s how it started, mainly because the technology wasn’t fully understood. Later, as techniques improved and evolved, particularly with the advent of the "Williamson Type", designers began to apply negative feedback (back when tubes were still dominant), as it improved every parameter except one. Distortion decreased, output impedance dropped, increasing the damping factor with beneficial effects on low-frequency reproduction, and the bandwidth expanded.

Naturally, transistor-based devices were heavily feedback-controlled, and everything seemed to work perfectly. However, it was later discovered that avoiding feedback made the sound more pleasing, even though this approach pushed technical specifications to the edge of what could be considered high fidelity. But that’s the historical trajectory of audio. There’s a catch, though. In the lab, electronics aren’t tested with speakers but with equivalent loads. These loads are resistive, bearing no resemblance to a loudspeaker system, which presents a much more complex load. The audio industry has never standardized an equivalent RLC load; everything is tested in purely resistive terms, so it’s no surprise things usually perform well in that setup. What often happens is that on the test bench, engineers design a transistor amplifier with a 100 kHz bandwidth and a total harmonic distortion of 0.01%, only to realize later that the sound is unsatisfactory. The great designers of the time, McIntosh, Peter Walker at Quad, and others, were not unaware of this. However, the manufacturing constraints and commercial trends of the era often dictated the directio

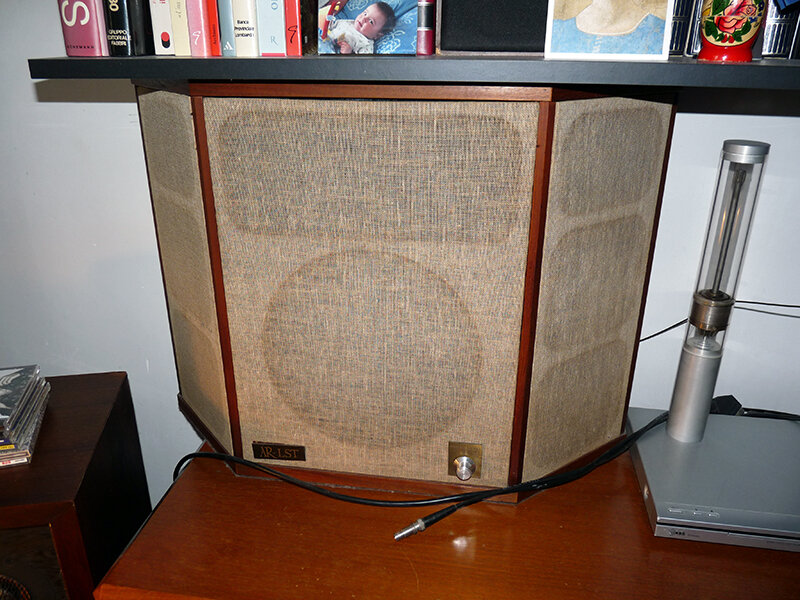

AR LST

Now, with the resurgence of Single-Ended designs, the refinement of components, and the ability to achieve sufficiently wide bandwidths without feedback, some remarkable amplifiers are emerging. The three tubes in the HDC 300B3 are pushed to their limits because when tubes are paralleled, significant design challenges arise. Parasitic capacitances add up, narrowing the bandwidth. Applying feedback to increase the bandwidth would be a simplistic approach.

We can realistically say that there’s a delicate balance between all these parameters, which is by no means easy to achieve. The right compromise must be found while avoiding feedback altogether. This is because the moment the output signal is fed back to the input with reversed polarity, the amplifier “sees” the speaker, an element that is dynamically overwhelming. The situation that feeds back to the input becomes, to put it mildly, highly complicated. The goal, therefore, is to design a good amplifier while excluding global feedback. This is why all my designs are feedback-free. McIntosh may have been the greatest amplifier designer of all time. In 1955, he developed a 60-watt push-pull tube amplifier using two 6L6 tubes. His circuit designs possess, in my opinion, an extraordinary elegance. However, they are all push-pull designs. From the U.S., we move to Europe, where the great Philips made, and continues to make, extraordinary contributions to the field. (Here, he shows me the book Low Frequency Amplification by N.A.J. Voorhoeve, a 1952 publication from the Philips Technical Library.)

Dorino's System

Turntable Acoustic Research XA - Cartridge Shure M97-XE - Preamplifier - Stereo Power Amplifier "Svetlana" - Stereo Cassette Deck Teac V-3RX - CD Player Tascam CD-RW5000 - CD Player NAD 502 - D/A Converter Cambridge DacMagic - Low Voltage DC Stabilizer SCB 321 BRS 1444 )